I have an obsession with the designs of one Richard Berg. Often fiddly and weird, I can’t give them all an unqualified recommendation, but I have always found Berg’s work interesting even when I don’t enjoy it. Within Berg’s prolific catalogue of designs, I have struggled with his Great Battles the most. Great Battles of the American Civil War (GBACW) is a system with a storied history, going back to Terrible Swift Sword from SPI in 1976. It was substantially redesigned into an almost new system, but carrying the same name, with Three Days of Gettysburg from GMT Games in 1995.

I have never played the original SPI version of GBACW (but I very much want to). My experience with the GMT-era of GBACW has been…fraught. I really disliked Into the Woods, and while I had a better time exploring Dead of Winter, I still would not classify myself as a fan of that game. However, I am almost always willing to give something a second try, especially if it’s a series that originated with Berg. So, when I heard that By Swords and Bayonets was meant to be a much better entry point to GBACW (something that Into the Woods very much was not) I was interested in giving it a try. Even if I didn’t expect to like it, because I think I’m just not a GBACW guy, I wanted to be certain.

GMT Games kindly provided me with a review copy of By Swords and Bayonets.

Let’s start at the beginning: what is By Swords and Bayonets? It covers four battles from the American Civil War, all of them relatively small engagements. You’ll only have a few dozen units on the map at most, and the maps are all half-size (22”x17”), so it makes for a compact package. For a series that’s probably best known for its huge battles across multiple maps, this is a deviation. It’s not a totally new thing, Valley of Death included multiple small battles, but it is unusual, especially in its commitment to being a manageable size. We will discuss this more later.

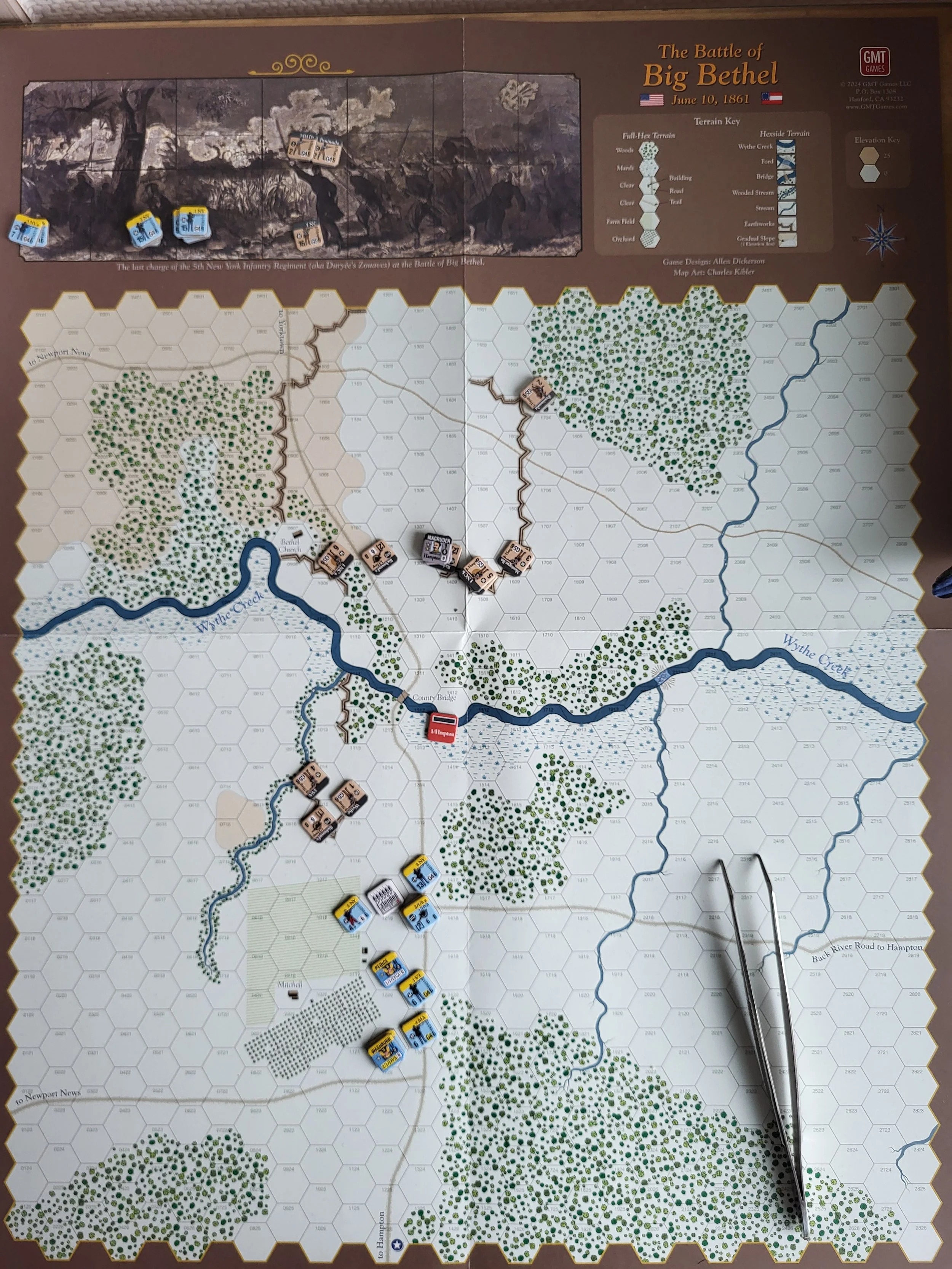

The totality of what is involved in Big Bethel, you can see a few Union reinforcements at the top of the map. It’s a cute little package!

However, while it is much smaller in scale, it is in no way smaller in rules. This is the full weight of GBACW, and arguably even a little more, as the technically optional fatigue and ammo rules are mandatory in By Swords and Bayonets. This is not an attempt to make a simpler on-boarding game in the same vein as, say, OCS Luzon, which stripped out a lot of core systems from the Operational Combat Series (OCS) series rules to make a simpler (and smaller) experience. By Swords and Bayonets is throwing you into the deep end, but the pool is a lot smaller, so while the depth may swallow you up at least you probably won’t get lost.

Reviewing a game like By Swords and Bayonets is a tricky thing, because it is partly a review of GBACW as a whole, since at least 90% of the rules are just the series rules to GBACW, but I am also trying to review this specific game because I’m by no means qualified to speak to GBACW as a full series.

In this review we will be spending a lot of time talking about GBACW as a system first, and then we will dive into By Sword and Bayonets, the specific game in this series.

Great Battles and Great (i.e. big) Rules!

Complexity in games can mean a lot of things. One type is where the game is hard to comprehend – it does something unusual or in some other way it is hard to move from rulebook to game. I associate this sort of complexity most with the designs of Volko Ruhnke – series like COIN and Levy and Campaign make a lot of sense once you know how to play them, but it only looks that way once you are on top of the hill after the initial steep climb that the rulebook presents. While I often bounce off these kinds of complex games the first time I try them, I do usually like them. GBACW is not this kind of complexity.

GBACW is the kind of complexity where it has so many rules. It is incredibly dense, and it’s dense in basically every direction. While something like Dean Essig’s OCS dumps much of its complexity into one area (supply) and leaves other areas (combat) very simple, GBACW is complex everywhere. No individual rule in GBACW is necessarily that complex on its own, but it often has several narrow exceptions to those rules, and each rule is built upon layers of other rules. The whole thing is a lot to digest.

You can see the legacy of this system in its rules, as more and more material has been added. Players have clearly found areas where earlier rules caused problems, and the system has been patched extensively to clear up any ambiguities, which helps ensure the system runs smoothly but does mean that there are yet more rules to remember. There is nothing wrong with this necessarily, but in GBACW it reaches a rather extreme form.

In contrast to By Swords and Bayonets, this is what the smaller scenarios from Dead of Winter look like - it’s a lot more.

Whenever I am playing GBACW, I have this sense in the back of my mind that there is a rule that would apply here, but I can’t quite remember what it is. Forgetting rules is a part of wargaming, and you can’t let that stop you from playing the game, so that’s not new. However, I struggle to even know where my mistakes are because GBACW is so expansive. I can’t just flip open the rulebook to the relevant page, because I’m not sure where in the 40+ pages of rules is the piece I’m overlooking – and I think that’s because the complexity is everywhere. For each unit activation I have to wonder if I’m missing something in the movement rules, the fire combat rules, the shock combat (if I’m doing one), or maybe I forgot a rule relating to chain of command or number of activations each unit can make. The only way to know would be to re-read the whole rulebook, again.

Some things could be improved to make this more manageable, especially in the play aids. The play aids are serviceable, they have the core information you need on them, but the layout is very bland and it could use more information. For example, there is no sequence of play on the player aid, and that’s pretty important! There are lot of steps involved in building the chit cup at the start of the turn, and things that can be overlooked in that process. Shock combat is a multi-stage process, and it’s easy to overlook one of those steps. The rulebook does try and point out rules you might forget, but as you’re absorbing pages and pages of rules it’s hard to remember the reminders and so having them on play aids would be a big help.

While I’m generally not a big fan of how Great Battles of History (GBoH) has two play aids per player, I think having a second play aid with more reminder-based information (sequence of play, detailed breakdowns of steps for shock combat, etc.) would really help new players with GBACW’s complexity. Seasoned veterans could safely ignore it, but people like me who can’t remember exactly how withdrawal before shock works would be reminded that it exists.

Getting rules wrong is part of wargaming, so it’s important to not panic when you get rules overload. These games are complex but they are often quite robust, meaning that getting one rule wrong rarely breaks the experience. You just fix things as you go and embrace the experience rather than getting it entirely right every step of the way. Even seasoned wargamers keep the rulebooks close by to look things up. However, writing reviews of games is a weird thing – I’ve played a lot of games and I feel like I’m pretty confident when it comes to knowing how to play a game. However, I’m also naturally concerned about playing a game wrong and then showing off my error to the wider community, which can make the experience of not knowing a rule frustrating – especially in a game that I find frustratingly complicated. That’s a me problem, but this is my review, so you’re going to hear about my problems.

The Good Battles of the american civil war

Now, amidst all this complexity there are things that I really like about GBACW. While I may think that overall, this system is too complex, and would maybe be improved by being more focused on a specific aspect of ACW combat, here are my favorite systems where I think the complexity works. They are: the chain of command, fatigue, efficiency and the chip pull system, and the orders.

Chain of command, efficiency, and orders are all very closely intertwined. In a game of GBACW you have your various officers represented as counters on the map and you need to make sure that your officers are within the command range of their direct superior. This will enable them to more easily change their orders at the start of a turn and to activate the maximum number of times they are allowed – out of command units will generally have one fewer activation in a turn, which can be a big deal, and some in command units may get extra activations if their superior officer is good enough.

GBACW is a chit pull system where you draw a chit from a cup and it tells you what division will be activating. You do this until the cup is empty, and then start a new turn. A pretty common system. In GBACW there is a little extra spice in that at the start of each turn you draw an efficiency chit from a pool determined by the scenario, and it tells you how many chits for each division you put into the cup. This adds a layer of randomness to the number of activations in a given turn, and I love randomness in my chit pull games. Properly you are supposed to hide your efficiency draw from the other player, so you don’t know how many activations each enemy brigade has, but I’ve never felt confident enough in GBACW to do this. For more advanced players I can see that being interesting, but for me I’m too much of a struggling little child to also do that.

When a division activates, each brigade in that division operates under one of four orders: attack, advance, march, or reserve (this last one isn’t technically one of the orders, but I feel like it kind of counts as one). Each has benefits and restrictions, and in an ideal world you would jump between these as you want (and some systems, like Blind Swords, basically let you), but in GBACW if you want to change orders during a turn you have to roll and your leaders may not do what you want. This helps to reinforce the idea in GBACW that you are the overall officer trying to give orders, and you have to work with the officers in the field that you have. You set the orders for the turn at the start, because that’s when your messengers are dispatched, and later changes rely on individual officer initiative. It’s thematic and interesting, and generally not too overwhelming to track.

The markers can get pretty involved - here we can see Attack Orders markers (Advance is considered default, and requires no marker), units have strength markers under them and one unit is Collapsed. On the right is the activation chit for the Union. Please ignore how I think I screwed up stacking in this scenario, I was struggling.

Fatigue is an optional system, except in By Swords and Bayonets, but I would recommend it to anyone interested in GBACW. If your units activate too many times in one turn, or engage in basically any sustained level of shock combat, they will gain fatigue and as they gain fatigue they will become worse. One problem I have with many ACW games is that the soldiers are kind of like robots – able to attack forever without ever facing the exhaustion of actual combat. Combat wasn’t an all day affair in the Civil War, you often only got one or two big attacks out of your units. GBACW’s fatigue system works to fix this common problem and while it’s maybe a little more fiddly than I would like, I think it adds a lot to the tempo of the system.

Great (?) Combat of the Civil War

If GBACW really locked in on these systems and was primarily a game about command and control, managing your orders and pushing your units without overly exhausting them, I would like it a lot more. However, there is just so much more in GBACW. In particular, the combat completely overwhelms me in a way that I do not enjoy. GBACW has 15 pages of combat rules, it has another wargame’s worth of rules just in combat. That’s a lot.

The shooting combat isn’t too bad, it’s pretty standard wargame stuff. Most of the complexity comes from the fact that there are so many different kinds of guns, each of which has its own dice roll modifiers (DRM) at different ranges, and then there is another long list of further DRMs, with maybe even more scenario specific ones. This isn’t mentally challenging, but it can be slow to resolve as I have to calculate all the different DRMs, and I don’t find that very interesting. Berg is notorious for his numerous DRMs, so I can’t really complain as a Berg fan, but I will anyway - this is too many. I like DRMs, but I have a limit. There is also some extra complexity when large units are involved and in relation to stacking units and trying to fire at multiple units from a single hex, which gives me a bit of a headache, but if you’re prepared to play kind of badly (and I am), you can kind of avoid these rules by just shooting from one unit to another.

Shock combat, however, has many steps and phases and there are some very important elements that are easy to overlook because of that complexity. I think shock combat has interesting elements, especially when you add in things like fatigue to the system. In particular, I really like how engaging in shock combat disorders all the involved units regardless of outcome, that creates great tempo challenges as a player. Add to that the fatigue penalty for a brigade that engages in shock combat more than once a turn and you get the idea that you should be doing this sparingly, even as it is a crucial tool in your toolbox. However, I find shock combat so involved that I kind of just don’t want to do it.

This is very much a matter of taste. The thing I love the most about hex and counter gaming is movement, the careful positioning and movement of pieces. What I don’t like is resolving long, multi-stage combats. This was my problem with Great Battles of History, and it’s just as true of Great Battles of the American Civil War. When I am playing GBACW I enjoy the part where the lines move towards each other, but then the scenario reaches a point where I’m just going to be resolving attacks for most of the rest of the game and I deflate like a large comical balloon. I can see through its many systems that there are decisions to be made, and some of them are probably interesting, but the ratio of decisions to resolution is out of whack for my personal taste.

Also, GBACW has like a page and a half of rules for cavalry charges, and I don’t see the need for that much in terms of rules. Please, we don’t need this.

The goal of broad-level simulation is clearly on display in GBACW, and for some people that will be enjoyable. If you like working your way through a game as a process, and if playing a game with the rulebook open on your lap sounds like a great time, then there is a lot to offer here. This system is a lot, and it also clearly has a lot of depth if you are prepared to dig through it, but for me… it is too much. I have enjoyed heavy hex and counter systems, but this kind of heavy simulation-ist in all directions stuff just does not work for me. It’s too broad, there’s too much, and for me the specifics of the argument or idea it is trying to discuss gets lost in the too much-ness of it all.

Now, on to By Swords and Bayonets.

By Swords and Bayonets is a smaller scale offering than most entries in the GBACW series. To adjust a system originally built to model Gettysburg to something on the scale of a Big Bethel requires some changes to the system – although thankfully By Swords and Bayonets keeps the changes to core rules relatively light. However, some of the battles include 4+ pages of specific rules, which is a little imposing, but I’m generally more forgiving of battle specific rules. While I think they could be simpler (why are the rules for when the rain stops in Mill Springs so long?), I was never baffled by any of them, so the extra chrome was generally welcome.

I love scenarios where the two armies start some distance apart and have to move closer, especially with a bit of harrying (in this scenario provided by skirmishers). This kind of set up is like catnip for me.

Very few rules were removed from the core of GBACW, which we’ll get to later, but one thing that was simplified was the chain of command. No corps commanders are present for these tiny battles, to say nothing of overall commanders. This means the chain of command is necessarily a lot simpler and plays a far less important role in these battles. In general, I support removing this layer to make the game’s simpler and better represent how these battles were managed by their respective armies. However, I like the chain of command system, and it being partially absent in this entry, while logical, makes it a little less fun for me.

With that said, I quite like the scenarios in By Swords and Bayonets. Big Bethel is maybe a little too simple to be particularly exciting, but as a first scenario this is forgivable. It’s got enough bits to make you practice some of GBACW’s core rules (and the walkthrough in the examples booklet helps a lot with this), and there is enough potential options in the scenario to make it worth replaying for the more competitive players (which I am not a part of, but y’know).

However, the later scenarios inject some more interesting options (at the cost of greater complexity) and create some interesting situations. I quite like the rain conditions in Mill Springs. They make it so fatigue never decreases, which makes the fatigue system very important and introduces a different puzzle into an already interesting map to create a very different experience from Big Bethel. The battles feel like more than just the same game on a different map, which is what I look for in games with multiple battles and I think is a hallmark of good design in the Berg-ian tradition.

The Union got lucky with its rolls to wake up and notice the approaching Confederates, but the rain still made their response very slow.

I was also impressed with the research on display in By Swords and Bayonets. One gripe I have with many ACW games is that they don’t include bibliographies or other reference materials showing the designer’s research. That is not the case here – each battle has its own list of sources and there is a lengthy set of design notes at the end of the battle book. I love to see it.

These are pretty obscure battles, ones that most players probably won’t know very much about, so including material for further reading in addition to the brief summary of the battle is a really nice touch. While on the one hand I think this kind of material should be a minimum for the hobby, currently it isn’t and so I want to praise it when it is here, so By Swords and Bayonets receives kudos from me.

There is a clear eye to scenario balance in the victory conditions for the battles. It reminded me most of the scenarios from Great Campaigns of the American Civil War, which I had kind of a mixed feeling about. I appreciate that for those who want a competitive experience, this is great, but for me, as someone who does not care very much about winning historical wargames, these just feel like more faff than I care about. Thankfully they are easily ignored by people like me, and they are there for people who want them. So I can’t really complain.

The graphical design, especially for the maps, is excellent. Charlie Kibler really knocked it out of the park with these maps – they are gorgeous and (especially for Mill Springs) they include some useful guides for play as well. The field of maps for ACW games is very competitive, there are some phenomenal maps, but for me Charlie Kibler is the best currently doing it, and By Swords and Bayonets is another excellent entry in his catalogue of work.

This is where it began to lose me - the lines have met and what remains is a lot of combat. Carefully planned combat, sure, but I feel more like a computer doing that than a player.

Beginner Battles of the American civil war

Now, let’s consider how well By Swords and Bayonets works as an introduction to GBACW. To put it simply, I think it does an okay job.

It doesn’t simplify GBACW at all, so you are learning the full rules to play it. That means it demands a lot of you before you can start pushing counters on that hex map. Still, it is a much smaller scale and offers a robust gaming experience for fans of this kind of system, especially for people (like me) who may not want to play one tiny section of a bigger battle. I would still very much prefer a game that streamlined some of GBACW’s elements (all battles without cavalry, so you can ignore all the cavalry rules, for example) than one that tosses you in deep.

That said, this is probably still the best place to learn GBACW, especially among the currently available options. It’s much easier to learn than Into the Woods, which has so much extra material in the battle book you might drown, and its much cheaper (and more in print) than Valley of Death.

If you were on the fence about GBACW and its staggering complexity, I don’t think that By Swords and Bayonets will be enough to change your mind. Spoilers for the conclusion of this review, but it didn’t really change mine. However, if you have always wanted to play GBACW and you like these kind of heavy as hell tactical systems, then this is absolutely a great place to start. You can play these battles in an evening, and that’s nothing to shake a stick at. For fans of the system, I think this is probably a great package, and for fans of this kind of thing the same is likely true. However, for skeptics or people who have struggled with earlier volumes in the series, this is still GBACW in all its hefty glory (and rules).

Great conclusions of the american civil war

I liked By Swords and Bayonets best of any of the GBACW games I have played, but at the end of the day I couldn’t say that I actually liked it. Every turn I took, I did things that I liked, but I also felt like I would be liking it more if it was a simpler and/or more streamlined system. Especially when the lines met and I had to spend activation after activation resolving combats, I yearned for a simpler system.

I am also not convinced that the greater complexity creates a more valuable or historically rigorous simulation for these games. I think they are for people who like processes and enjoy that nitty gritty detail. GBACW is certainly a system that would appeal to rivet counters, but I wouldn’t be so harsh as to say that it is only for rivet counters. I fully believe that many players see a detailed and evocative narrative in the systems and their many layers and exceptions, but for me I just see the rulebook and me scratching my head as I try to figure out whether I’m missing something or not.

GBACW is for someone, that much is clear. That person may be you. It isn’t me. I just don’t want this many systems in my games – when my games are complex, I want that complexity to be more focused and following a narrower thread. Where there is complexity in a system, I want it to be counterbalanced by simpler systems in other places. GBACW is complexity everywhere, including in places I do not want it to be, and that’s not for me. By Swords and Bayonets puts GBACW into a smaller, faster playing package but it simplifies nothing, so it remains just too much for me.

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)