Like many people I imagine, I first heard about Verdun 1916: Steel Inferno from a livestream on the Homo Ludens YouTube channel, where several prominent designers of card driven games (CDGs) highlighted it as one of their favorite games in the genre. However, many years, and a second appearance of the game on Homo Ludens, would pass before I played Verdun for myself. I long held off on buying it, for lack of anyone to play CDGs with (I, for one, don’t love soloing CDGs), but I was given a copy in a Secret Santa for Christmas 2024 and set myself a goal of playing it. I initially struggled and it sat neglected on my shelf, but I was finally saved by the addition of Verdun to the excellent website Rally the Troops.

I no longer had an excuse, so I set about learning and playing as many games of Verdun as I could over the winter break in 2025 (and in early 2026). Even with around half a dozen games under my belt now, I still feel like a novice. While not a complex game, there is clearly a lot of depth to Verdun, and I can feel my own lackluster skills every game I play.

On the whole, I am incredibly impressed with Verdun. It is an incredible piece of design and a beautiful game with some lovely touches in terms of how it represents the conflict. However, I’m not sure I love it. I believe it is capable of being among many people’s favorite CDGs, but I’m still trying to figure out if it could ever be one of mine.

it’s about the cards

Verdun is a relatively simple CDG – a genre of historical game where players have hands of cards that represent both historical events and generic operation points that can be spent to take actions. On your turn you must choose between playing a card for its event, possibly removing it from the game, or for the operation values printed on the card. In Verdun, the operations focus on moving your units on the map, refreshing exhausted troops, and building trenches. It is for performing the logistical work that underpins your campaign, while the events can give you bonuses or one-off powers. However, most of the decks are made up of barrage cards.

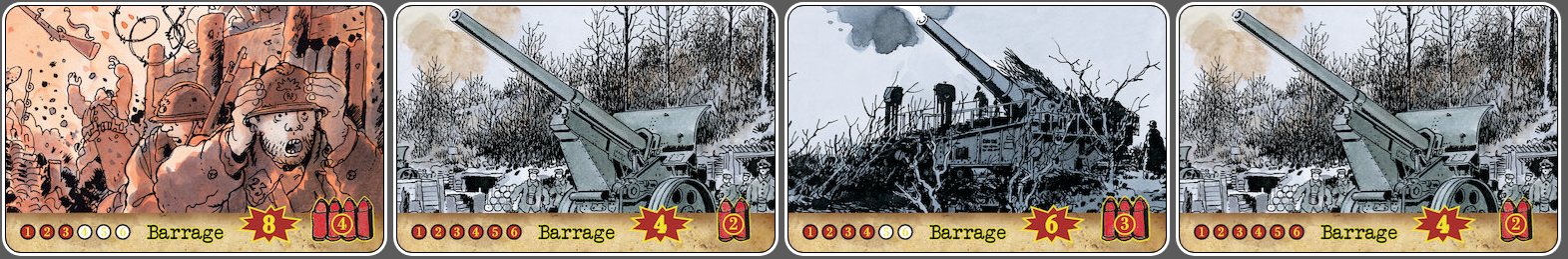

The barrage cards are really the heart of the game. You can only make attacks when you play a barrage card – or you could play two barrage cards together, to either increase the potency of your attack or to attack two places at once, but at the risk of not having cards to play later in the turn. You total up the value of your barrages, subtract any value played as counter barrage by your opponent, and you roll that many d6s. Every 4+ is a hit and you can re-roll any 6s to look for more hits, but every three 6s causes a hit to one of your own units due to friendly fire. Hits are reduced by enemy trenches and fortresses, and then are used to exhaust and ultimately maybe eliminate enemy units before you resolve your infantry assault. Infantry combat is entirely deterministic, with no die rolls or randomness at all.

Barrages come in different values, and the higher value the barrage the more action points it could be used for if you choose to not shoot those guns. Here we can also see the turns that these cards are available to the German player, with the highest value ones disappearing from the deck later on.

There is a lot of randomness in the barrage dice, but you will be rolling so many over the course of the game that you shouldn’t suffer from unfortunate strings of bad luck. You can also always predict how infantry combat will be resolved, so that gives you some reliability to consider when planning your attack. However, you shouldn’t put all your hopes in one attack and bad luck will happen, your plans need to be robust enough to absorb those bad turns of fortune.

The dice rolls can also be modified by your Air Superiority value. If your planes rule the sky, you can ignore hits to your own units on rolls of too many sixes and possibly re-roll a particularly bad barrage roll. With enough superiority you can hamper your opponent’s barrages as well. The cost is that to gain Air Superiority you have to play event cards that do nothing else but move the air superiority pawn one point closer to your side. That’s spending a whole action (and a valuable card) doing nothing else, but Air Superiority is so good you will want to do it whenever you can.

know when to hold ‘em

At the start of each turn, you search for a card in your deck to add to your hand before blind drawing the rest of your cards. So, if you need Air Superiority maybe you use this opportunity to dig out one of those cards to ensure you can shift air power in your direction. I was initially worried this searching mechanic was going to be clunky – lots of CDGs have huge decks of cards and asking players to identify what cards are the best ones right out of the gate (or at least, from the second turn, first turn hands are set in Verdun) is a big decision you must make with little information.

However, Verdun constantly changes the two sides’ decks to reflect the shifting campaign – with the Germans starting strong but losing momentum while the French deck grows in strength in the late game. One knock on effect is that the decks are rarely that big on any given turn, and a huge number of those cards are barrage cards, so the pool of events you are picking from is much more manageable than I had feared. It is not a rule that I think would work for every CDG, but in the wider structure of Verdun it adds a great bit of player agency to the randomness of the card draw.

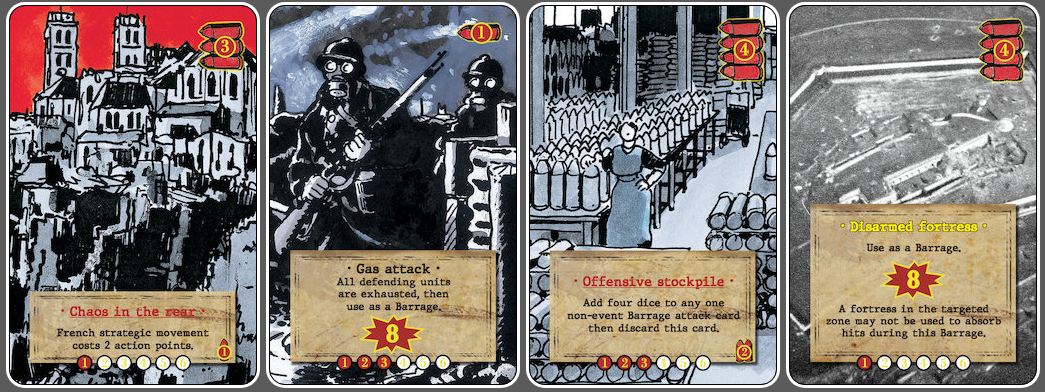

Verdun sometime asks you to sacrifice tempo for events with longer term impact. I already mentioned Air Superiority, but there are other events that are played with minimal effect at the time but unlock key conditions for later. The French player has several events that need to be played, sometimes with negative effects, that then springboard and enable the play of powerful events later in the game that require those earlier cards be in play. I’m not entirely convinced by this system – I appreciate its effect in the big picture, but it feels a bit clunky. This idea of sequencing events is not new to Verdun, it exists in other CDGs, but in a game that feels very tight these just feel a little awkward here.

A full display of key French event cards, you can see the cards they combo with written on the cards and by late game they can enable some amazing French attacks.

I think it also stretches the abstraction of the CDGs. Many of these cards are personalities, but I’m not sure what that means in this context. For example, one of them is Field Marshal Haig, who was not at Verdun. He is connected to the Somme Offensive cards, because Haig ordered the Somme Offensive in part to remove pressure from Verdun, but I don’t know what playing him in the game represents. It’s one of several ways that events outside of Verdun, but which nevertheless impacted on the battle, are abstracted onto cards. I appreciate the wider narrative they add, but I’m not convinced by the abstraction.

Some of these events work really well – I think the one-two punch of submarine warfare and US intervention cards, where playing the former gives a bonus to the latter, works great – but others, mostly the ones where you roll a die to see if you get or lose VPs, don’t feel as tightly refined as the rest of the game. They are particularly subject to luck, because you won’t be playing them enough for the luck to necessarily even out over the course of a game, and they just aren’t all that interesting. Roll a d6, gain or lose VPs, just isn’t that interesting.

Don’t get isolated

Verdun has a punishing supply system, where units that are cut off from friendly lines can’t attack, so they can’t fight their way out, and will be eliminated in only a few short card plays. Because actual assaults are so unpredictable, it is far better to cut off exposed units than to kill them directly. This also makes it very hard for the attacking player (first the Germans then the French) to exploit a break in just one point in the enemy lines. You need to breach your enemy’s position in multiple points to guarantee success, because if you push down one narrow line you expose yourself to being cut off and losing all those units.

Verdun is a game of tempo first and foremost. The German player is on the offensive at the start and has to seize as much territory as possible. They start the game with more powerful barrage cards and with more troops on the map. They also get to decide where the attacks will happen and can keep the French player on their toes, trying to guess where the next assault will come. However, as the game progresses the German player will lose their best barrage cards from their deck and instead gain weaker No Event cards, often with evocative art and descriptions around things like resources being busy to bury the dead, while the French artillery will finally arrive and enable a major French counterattack.

This was my lone German victory, where I had pushed the French pretty far and stalled their counterattack. I love how messy the lines become over the course of a game.

Many wargames have used this structure many times. What makes Verdun stand out is how it uses reinforcements. Players can spend action points to bring on more units, but to do so they must also pay one victory point per unit that they bring up. They can bring almost infinite troops – limited only if all the wooden pieces are on the board already – as long as they are prepared to pay the cost. This gives players a lot of agency and makes the decision of how to push against and react to attacks far more interesting than in many other wargames. You can always throw more soldiers into the breach, but is it worth spending those victory points to bring in units so you can take this one hill? Is this fortress worth 3 VPs to you? It makes a decision out of something that many games treat as automatic – tradition is to have the arrival reinforcements exactly mirror what happened historically. Instead of doing that, Verdun sets out to evoke the decision space of the commanders, asking you if you can afford to pay the cost of defending or taking Verdun.

Reinforcements also directly feed into the game’s morale system. If your morale drops too low, due to suffering horrible casualties, you will lose the ability to make attacks or even play barrage cards. Bringing new soldiers onto the map will rebuild morale – these guys haven’t seen the horrors of war yet – but every time you do you are spending victory points, which feels awful. But if you can spend victory points to make the other guy spend victory points to bring even more troops on to deal with your troops, well then, they’re basically free!

Endgame is hard

While I’m no great Verdun player, I have found it to be much, much harder as the German player. You need to really obliterate the French in those opening turns to have a chance at winning once the French counterattack comes. Even if it feels like you are doing well around the mid-game, things can collapse very quickly. That said, you never feel all that comfortable as the French player, as the weight of that German offensive leaves you scrambling to patch up your lines. It made me feel stressed playing both sides, which is impressive.

While I admire how Verdun manages to make it feel like things are going badly as both players I’m not sure it always lands as a satisfying endgame. As the German player, it can become pretty apparent that you didn’t do enough to win several turns before the game ends, and turns in Verdun, while not eternal, aren’t exactly short. I can’t help but wonder if the game would be better with a mid-game victory check, to bring an early end if the game is all but decided by then. Of course this would deny the French player the experience of launching their own offensive, which might be underwhelming for them. This is certainly more of a personal taste thing, but it’s my review so you get my taste!

they all have lovely arts

This is an incredibly pretty game, which is obvious to anyone who has seen it. The card art was all done by the French comic artist Tardi, who has done several works on WWI before, and it really helps Verdun stand out. The cards also have excellent graphic design for usability, so it’s both functional and beautiful.

Look at these cards! Just look at them!

Instead of specific counters or pieces to represent specific historical units, Verdun uses generic wooden blocks to represent all units. While it removes some of the historical flavor you usually get in wargames, I think it is an inspired choice. It makes the game look distinct and gives it a lovely tactility (I love blocks in games), but it also allows it to tell a its story better.

As we can see in the reinforcements system, Verdun splits itself from a narrow representation of the history and instead shows the faceless violence of the battle. It lets you think about the battle in a bigger picture and zooms you out to the perspective of a higher-level commander who doesn’t know the individual soldiers, rather than locking you into a retelling of historical facts. The generic blocks are faceless units you are sending to their death and the game really puts you in the shoes of someone who is responsible for these people’s lives but doesn’t know who they are.

I also think the board is both really pretty and very usable. It’s a great presentation overall.

To Conclude

I have had a complex relationship with CDGs over the years. My first historical game was the original CDG, We the People, but I have also really bounced off some of the genre’s entry – most recently Tanto Monta but also more venerable games like Wilderness War. Verdun hits CDGs at exactly the level of complexity that I love and makes excellent use of this genre’s titular mechanism. This is an amazing entry in the CDG genre.

All that having been said, I don’t know that I love Verdun, and I think a lot of it comes down to the game’s tempo. The game is just a little too long for me for that back-and-forth to land for me. The fact that it’s so hard to be the Germans means that the second half of the game often fails to deliver a satisfying experience. The game can be taught to anyone, but it takes several games to really open up and you have to be prepared to dig into the game’s trenches to get the best experience. Even with quite a few games logged, I feel like I’m still not there yet.

Maybe I have to confess to being a bit of a loser dabbler rather than a hardcore devotee, but I think Verdun asks of me more than I can give it. While I admire it, and I will probably play it again, I don’t know if Verdun will ever make my list of favorite CDGs. Still, if you are a fan of the genre, you absolutely should play Verdun 1916: Steel Inferno. Maybe it will be your new favorite game, and even if it’s not, at least you will have experienced a fascinating game, and what more can anyone ask from this hobby?

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi or supporting me on Patreon so I can keep doing it.)