I was lucky enough to receive a copy of the Musket and Pike Dual Pack by designer Ben Hull as part of the BoardGameGeek wargame Secret Santa this past Christmas and I am very excited to have it. I’ve always had a bit of a soft spot for this era of warfare and the GMT multipacks are a great way to get a big helping of a system for not too much investment in money or space (the former obviously wasn’t really a concern since this was a gift, but the latter always is). On top of that, the Dual Pack is a stunning production. The maps all have this lovely linen finish, and the counters have new art in a woodcut style that I adore. Also, there are double size counters and I love double size counters. It’s just a very nice object to hold and manipulate, always something I look for in a game.

The system itself has something of a reputation for being on the heavier end, certainly heavy than my main Hex and Counter squeeze Men of Iron but lighter than some systems I’ve played. I had an interesting time learning Musket and Pike and I wanted to share my thoughts on getting into the system and trying to come to grips with it before I write any sort of review. I’ve muddled my way through about two games so far and I don’t feel like I have anywhere near enough of a grasp on the system to be writing a review, but I hope that my thoughts on learning it may be of interest and/or help to people who are similarly interested in this system and setting.

Learning the Rules

The rules for Musket and Pike are a mixed bag. I found the actual text of the rules very clear, there were a good number of examples. It was easy to read while also providing the necessary clarity to ensure that I felt like I understood what the game’s intentions were. The problem lies in the order in which the rules are introduced. I don’t really understand why the rulebook is laid out the way it is, and I found the way key concepts were introduced confusing. For example, the rules for movement only appear halfway through the rulebook – you learn all the rules for Reactions before Movement, which just felt very backwards to me. I’m sure this order makes sense to some people and once you know the system and are only referencing the rules it’s not a big problem, but it was a barrier for me.

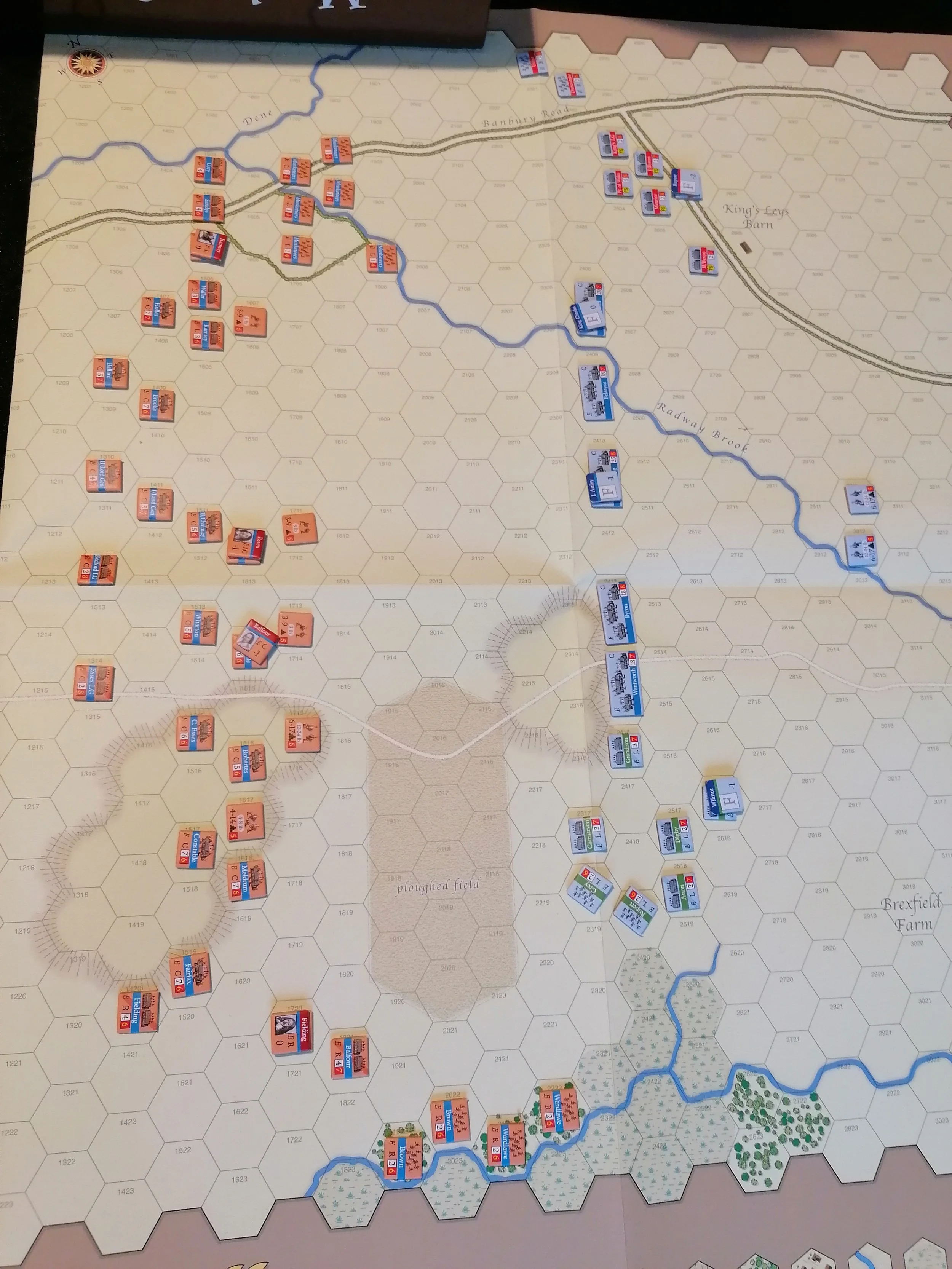

The stacks can get pretty massive when you add together formation hits, damage, morale hits, whether the cavalry has used their pistols, etc. Thankfully this seems to be more the extreme than the norm.

Musket and Pike includes a lot of elements that were new to me, or that I had very little experience with. The rules for unit formation, where combat and terrain can degrade a unit’s capabilities until they are rallied, are really interesting. The impact of terrain stretches beyond just a higher movement cost and makes each feature on the map impactful. It also raises some pretty significant tactical challenges.

I haven’t played a game with this many options for Reactions. Men of Iron lets archery units shoot during the opponents turn and has some limited counter charge ability, but Musket and Pike has more of both as well as reaction moves and withdrawals. This makes the play feel much more fluid, where you can swap freely between the active and non-active player. It also takes a bit of time to wrap your head around all the implications of what moving a unit somewhere could be, as it could trigger any of a number of reactions from the other player.

Musket and Pike does not have Zones of Control. I have technically played some games without Zones of Control (Men of Iron claims it doesn’t, but it does), but nothing on this scale or of this complexity. Particularly when combined with the rules for units in Charge orders and how they must prioritize their movement, this required a new mental map of what a good unit formation looks like.

Lastly, Musket and Pike has a much more involved Orders system than I’ve usually played with. The nearest thing I can think of is Great Battles of the American Civil War (GBACW), but even that didn’t seem to place quite the same emphasis on changing orders. Musket and Pike even determines initiative based on what orders your formation are in, and orders are on a Wing level so there isn’t a lot of granularity available like in GBACW. Switching orders is also quite hard, so there’s a lot of thought required when it comes to picking what orders you want to be in as that will play a huge role in determining what you can actually do on your turn. Once you commit to a certain order you may be stuck in it for the rest of the game, so you really need to be prepared to make that commitment.

Putting it Together

After reading the rules I thought I knew how to play Musket and Pike. How foolish I was. Once I set up my first scenario, I realized that I had no idea how to actually play the game. This is an experience I strongly associate with the designs of Volko Ruhnke: understanding the rules is only the beginning, putting it together into actionable gameplay is an entirely different matter.

This really doesn’t look like it should be so intimidating and yet I had it set up for days before I managed to actually make a move.

It’s not that I’m worried I will play badly, I just have no grasp of what even basic tactics look like. With no ZOCs and various options for orders, what does a good formation for my units look like? How far should I move these units forward? What reactions will I trigger if I move that far? This is before we even think about things like Continuation rolls or the potential for interrupting an opponent’s activation or continuation attempt. There are so many decisions to make and I’m struggling to grasp even the most basic ones.

Take, for example, a unit that is deployed behind terrain that will give it formation damage when it advances through it. How should I manage their advance? If they are in Charge orders, because they started the scenario that way, then I can’t have them recover that disruption unless they change out of that order and stop their advance, but is slowly advancing across the map two hexes at a time and desperately trying to reform my lines a good tactic? Should I rush across the terrain and just commit to a messy attack? These decisions can leave me paralyzed.

Usually once I commit to actually moving the pieces the game smooths out and I have a better idea what I’m doing when it comes to reactions and counterattacks, but I still have no idea if what I did made any sense. This is compounded by the fact that the battles I played seemed to have far more turns than were necessary for my slipshod tactics. If a battle can last for twelve turns, but by about turn three I’ve already destroyed half of my army, it’s hard to not feel like I’ve made some kind of catastrophic error in my understanding of how the game plays.

The aftermath of two Wings colliding - a mashup of formation broken units and counter charges. I’m less certain of what to do at the top of the map where the hedges will disrupt units that pass through them.

None of this is strictly unique to Musket and Pike, it has just served as a reminder of how learning the rules to a game and knowing how to play that game are two very different things. I feel like I need to be coached through a game of Musket and Pike by a seasoned veteran to really understand what I am doing. I have tried watching some playthroughs, and I will probably try some more while muddling through a few more scenarios, but it can be hard to find the time to watch hours of gameplay videos and still manage to actually play the game.

Playing Solo

I’m also not sure about Musket and Pike as a solo experience. I think it’s perfectly playable solitaire, and I know people do play it this way, but with all the reactions and the open-ended nature of the decision space I find myself trapped in an endless ouroboros of indecision, planning turns within turns for both sides. Games that do this to me tend to not be my favorite for solitaire play, I want something with more immediacy. I prefer experiences like Blind Swords, where I draw a chit and just resolve that chit to the best of my ability in the moment.

The scenarios I’ve played so far also had an element of free deployment to the set up, which I can manage when playing solo but always makes me feel like the game is better with an opponent.

I will probably continue to experiment with Musket and Pike more as a solitaire game, as I become more competent, I’m hoping that this problem will decrease, but to better grasp the game I think I need an opponent. Unfortunately, I have far more time to play games solo than I do two player, so it will take me longer to dig through the many scenarios in the box if I’m playing it two player.

Conclusion

Overall, I think Musket and Pike is a really interesting system and one that I am very keen to explore more. I think once I can get the experience of playing it to feel like second nature I will have a lot of fun with it, but at the same time reaching that point will be a long journey. This is far from the most complex hex and counter game I have played in terms of just the rules, but the tactical implications of these rules have made it a much tougher game to wrap my head around than I had expected. Still, I love a challenge and this kind of complexity is preferable to me than a game that just dumps a load of systems and rules exceptions on you and claims to be superior because of it. Also, did I mention that it has double sized counters? I love double size counters.

(Hey, if you like what I do here, maybe consider making a donation on Ko-Fi so I can keep doing it.)