It definitely says something about me that I got very excited the first time I heard the title “Supply Lines of the American Revolution”. Growing up in Central Virginia, within spitting distance of the houses of many Founding Fathers and ex-Presidents, the history of the American Revolution played a central role in my early education and as someone interested in history it was impossible not to absorb some of the mythmaking that went with that education. Separately, as a military historian I’m always interested in the logistical challenges of warfare and the lengths commanders (and the institutions that backed them) went to wage effective war. A game that combines both of these interests was bound to be get me excited. It actually genuinely didn’t occur to me that the title might come across as painfully dorky until I showed it to my partner. Let’s be honest, though, if you’re reading this then you are probably of a similar persuasion to myself and the idea of pushing cubes of supplies around a map of the American Colonies fills you with excitement! So, what did I think of my first experience playing Supply Lines of the American Revolution: The Northern Theater, 1775-1777?

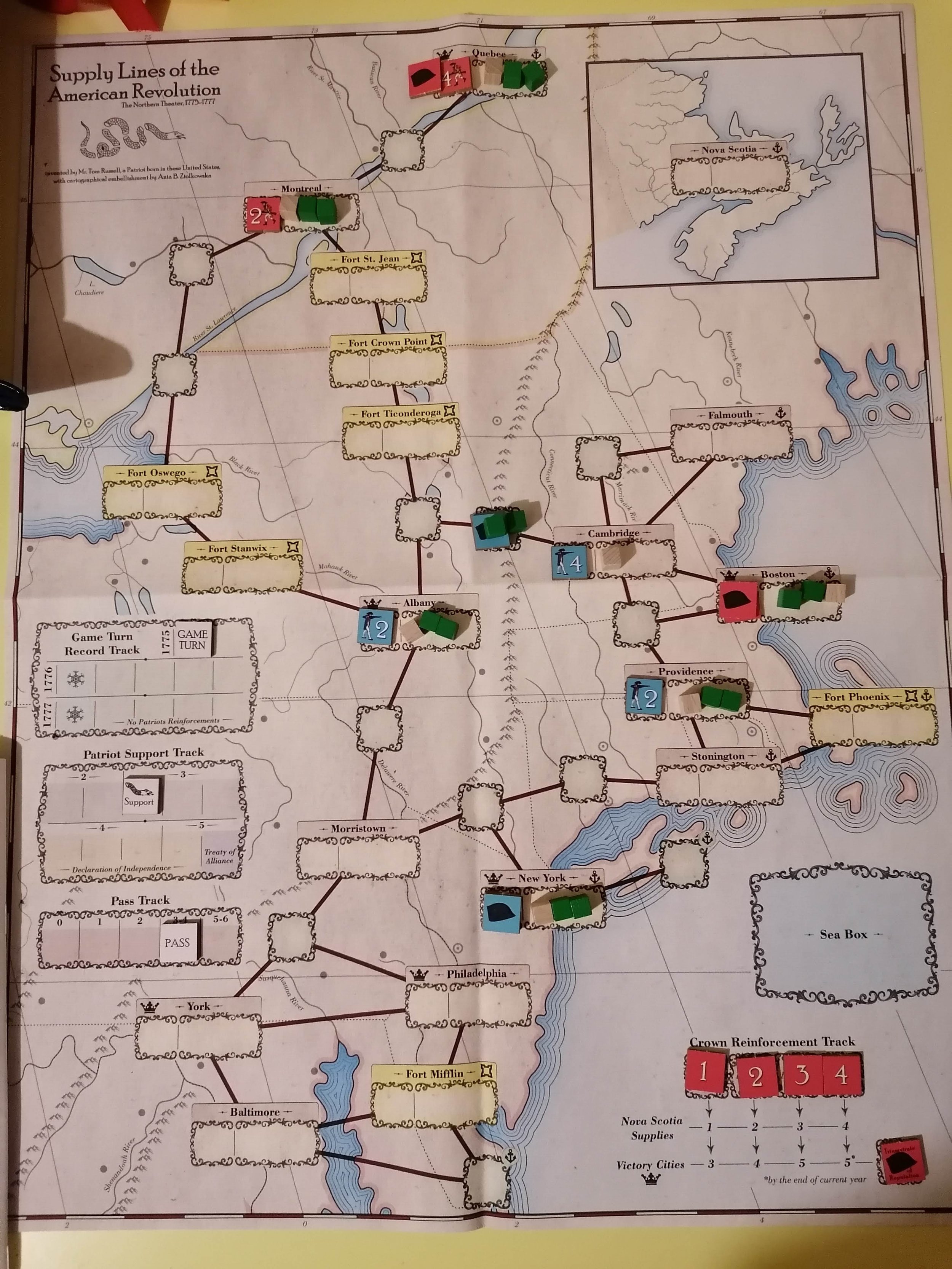

The initial deployment of Supply Lines with the first Supply Phase completed. While it may not look like much, I found the open-ness of the first turn quite overwhelming.

The core of Supply Lines of the American Revolution is the two types of resources that you have to manage: Food and Military Supplies. Food is necessary to move any of your armies. For every group of up to 4 units you wish to activate you must spend 1 food supply. That means you spend 1 Food for 1-4 units, 2 Food for 4-8, etc. Military Supplies become necessary whenever you want to fight - you must spend them to generate dice in combat (or, if you’re the British, to bombard port locations) which are necessary if you’re going to attack anyone or if you want to inflict any damage on someone who is attacking you.

End of Turn 1 - Revolutionaries begin establishing some initial supply lines and the crown seizes Cambridge and advances toward Albany. I was not fully prepared for how annoying maintaining the supply line down from Quebec would be.

On initial impression this isn’t too complicated - you need to spend cubes to do stuff. So far so Eurogame. However, things get thornier pretty quickly. For one thing supplies are only generated in cities that you have troops in (and that aren’t completely surrounded by enemy armies), but you need to get the supplies from the city that generates them to the front lines where you’ll be spending them. In the initial Supply Phase, when supply cubes are generated, you can move supplies across adjacent locations (up to a point) as long as you have armies at each of them. This gives you some ability to move supplies around and get them where they need to be, but the layout of the map and the distances involved can make this very challenging to manage. This is to say nothing of the challenge of assembling an army of any reasonable size when your troops are spread out over a great distance so that you can hopefully use all those supplies you’re generating at one end of the map.

Start of the first Winter Turn, the Revolutionaries have expanded out significantly but will soon face a severe reduction in troops as the Continental Army will disband. Meanwhile the British have called for more soldiers who will arrive with the spring.

One other interesting wrinkle in the system is that you can only attack if your army has a Leader with it and both sides only have at most three Leaders, so your ability to launch offensives is quite constrained. This creates a really interesting logistical puzzle because not only are you trying to get supplies from your cities to the front lines - you also need to get them to whichever armies have Leaders because only they can attack and push your opponent back. You also need to make sure that your leaders have a large enough army to still be effective - especially if you’re the Revolutionaries. The Revolutionaries win by generating support for their cause and bringing the French into the war. They do this by winning battles where a Leader is involved, but they can lose it every time one of their Leaders is defeated. I quite like when games do this - they give you an incentive to put key pieces on the offensive but also punish you if they are defeated. It makes for tense gaming experiences and encourages risky plays!

After the first Winter turn, the Continental Army disbanded but they receive extra reinforcements to make up for that, leaving them in a reasonably strong position thanks to some lucky draws. The revolutionaries also receive their third Leader. Meanwhile six British troops will soon be arriving in Nova Scotia. The war escalates.

Winning a battle is determined by the size of your army, not how much damage you inflict in combat, so attacking a small force with a huge army is almost always guaranteed to generate a victory. However, whether the defeated army retreats is based on a Morale roll, which introduces an element of randomness into attempts to seize territory. Larger armies also take more Supply to move and limit your ability to spread out across the map. This makes for a lot of tactical challenges and factors to consider as you play.

Things are looking up for the Revolutionaries. A few successful attacks fail to oust the British from Cambridge and Boston but they push the support track past the Declaration of Independence threshold. The British fail to capitalise on their new forces but are amassing for an attack on Ticonderoga in the north.

As should be apparent by now, I had a really interesting time playing Supply Lines of the American Revolution. It is a engaging puzzle and while it isn’t too complicated the punishment for messing up can be pretty brutal. In my game I screwed up the supply lines for the British pretty badly and they were never really able to recover. While it contains significant elements of randomness, from combat to the supply of new Revolutionary troops, the core of the game is the supply and I got the impression that the game is pretty balanced overall (if that’s something you care about, I’m not sure that I do).

The Revolutionaries succeed in taking Boston and attempt a flanking manoeuvre via the Great Lakes to reach Quebec. The British succeed in taking Ticonderoga but the supply line stalls out there and they must call in more reinforcements.

While it’s not exactly a criticism, Supply Lines is a game concerned entirely with the logistics of the war and so doesn’t really include much of anything about the political side of the American Revolution. Where a game like We the People tried to introduce more of a political dimension to gaming the American Revolution, Supply Lines eschews much of that to focus more narrowly on just this one aspect of the conflict. I think this is a reasonable choice, it’s a more interesting game in doing this one thing well rather than trying to do too many things and potentially becoming a bit of a bloated mess. Still, I think it is worth mentioning because this is very much a game that does what the title implies - it’s about supply lines - and people who prefer their wargames to be more about politics or diplomacy will not find what they want here. I enjoy games that include a strong political element but I also admire Supply Lines for just doing what it sets out to do. This also helps keep the game relatively short and simple (at least as far as wargames go).

The British succeed at retaking Boston but the Revolutionaries successfully encircle them to the north, isolating that Leader and making a push on Quebec possible. They are also just one victory away from the Treaty of Alliance which would bring the French into the war and marks a Revolutionary victory in this game.

A potential other criticism is that the game can feel quite abstract. I’ve used the word puzzle to describe it many times in this post and with it abstracting away all the politics there is a degree to which this game could just be an abstract game. I think the game map is doing a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of the theme, but at the same time I’m not sure how it could be any other way. After all, with a game where managing supply lines is the core mechanic, the layout of the lines is an essential part of the game. By having it be a map of the northern colonies during the American Revolution it puts an engaging theme on a game that could otherwise be much more abstract. I certainly felt like I was playing a game about the American Revolution in my one session of it, but at the same time I didn’t feel as drawn in as I have been with other games. The Leaders are nameless and the game isn’t structured to follow the historical narrative - you won’t be crossing the Delaware at the end of the game’s second year for example.

I think with both the abstract elements of the game and the lack of a political element these are things that would bother me a lot more if this were the only game on the American Revolution. It isn’t though, not by a long shot, and so I’m happy enough with it really only focusing on this one aspect of warfare in this period and discarding everything else to give a narrow but interesting experience. That said, it very much won’t be for everyone and that’s something to bear in mind if you’re thinking of buying it. At least the title very helpfully flags exactly what kind of experience this will be!

A successful Revolutionary attack on Boston gives them victory!

My initial play of the game was solitaire and I found that to be a good way to learn the game. While the rules are relatively straightforward there are enough little quirks and exceptions to track that it is more complex than would appear at first blush. Overall, though, I didn’t find it to be a great solitaire experience. As a game it works perfectly fine solitaire - there’s no hidden information or any of the other things that make games solitaire-unfriendly. That said, I found wracking my brain over the game’s logistical puzzle all on my own to be a bit exhausting and lacking some of the thrill I expect the game offers as a competitive experience. I think one could play this game solitaire and have a perfectly enjoyable experience, but for me I think I will prefer to play it two player whenever I can. It didn’t have the kind of narrative I want from a solitaire experience, unless me screwing up my supply lines counts as a narrative..

Not strictly relevant to the game, but I also found it pairs nicely with hot chocolate.

The series of games that it reminded me the most of was Volko Ruhnke’s Levy and Campaign games. Those are operational medieval wargames that focus on the logistics and supply of armies, although in significantly more detail and complexity than Supply Lines. While the theme is very different I think fans of one series should probably try the other - there is enough in common in the core experience of playing both of them to appeal to anyone who likes seeing their armies starve and fall apart because of mismanaged supply.